| ||

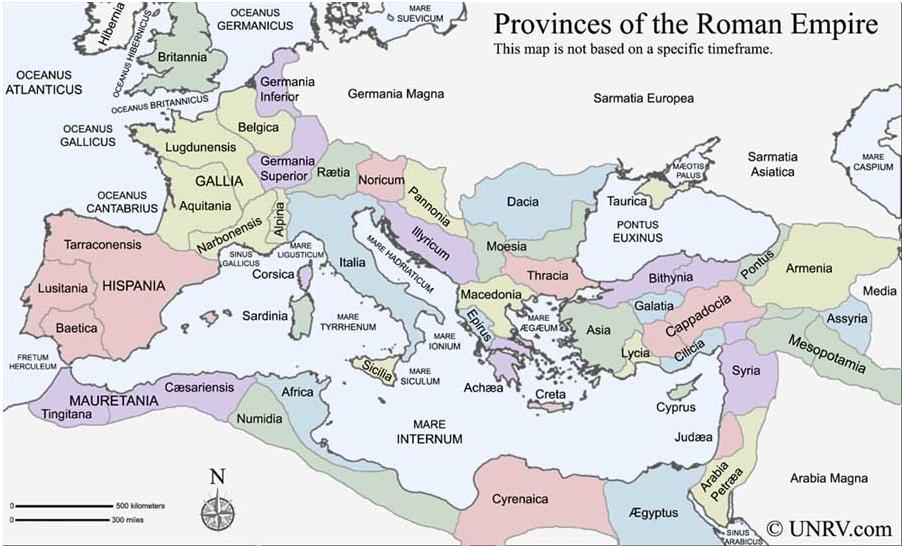

The logical end of this process would be a single language, and indeed there is evidence of a natural bias towards monolingualism: Firstly, the vast majority of bilinguals do not have an equal command of their two languages: one language is more fluent than the other, interferes with the other and imposes its accent on the other. * Secondly, whereas people tend to be better learners second time around, this does not apply with language. A second language is not nearly as easy to learn as the first, and seems to be learned in the context of the first. ** Third, most people in the world choose to be more or less monolingual and fail to properly maintain any multilingual opportunities that might have been offered to them at school. Fourth, an unused language tends to atrophy: the “use it or lose it” principle. Fifth, hundreds of millions if not billions of Jews, Christians and Moslems believe accounts in the Bible and the Qur’an about the Tower of Babel that present monolingualism in a favourable light, and many also interpret certain Scriptures, e.g. Zephaniah 3: 8,9, as pointing to a global monolingualism in the future. Such considerations are important because monolingualism is an obvious challenge to multilingualism. But what of the future? Would a global monolingualism be possible? To answer that question we might look to the past, and see how pan-national monolingualism has emerged. For instance, we know that Latin was widely spoken across a vast swathe of Europe by the end of the Roman Empire, and that the Romance languages resulted. But was it just the might of the Roman army and the force of Roman Law that brought this about? History suggests otherwise, and that the spread of Christianity across the Empire after the conversion of Constantine was pivotal in the acceptance of Latin as universal lingua franca.

* “The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language”, David Crystal, Cambridge University Press, 2nd Ed.,1997, p 364: “....People who have “perfect” fluency in two languages do exist, but they are the exception, not the rule. The vast majority of bilinguals do not have an equal command of their two languages: one language is more fluent than the other, interferes with the other, imposes its accent on the other, or simply is the preferred language in certain situations. For example, a child of French/English parents ..... Her linguistic competence certainly did not resemble that of monolingual teacher-mothers. This situation seems to be typical. Studies of bilingual interaction have brought to light several differences in linguistic proficiency, both within and between individuals. Many bilinguals fail to achieve a native-like fluency in either language. Some achieve it in one (their “preferred” or “dominant” language), but not in the other." ** Suzanne Goldin-Meadows in book review (Kolb, 1997): "One of the most striking facts about language learning is that the second language is not nearly as easy to learn as the first. The question is why. In most areas, people tend to be better learners the second time around. What is it about the way we acquire, represent or process language that makes us less proficient learners the second time around?........perhaps second-language learning differs from the first simply because it must be learned in the context of the first. The first language may set up patterns and habits that, at least in some cases, are inconsistent with the second.....age itself may be a factor. Many changes occur with age that could affect language learning and create the wide range of individual differences that are the hallmark of learning a second language—loss of ability to segment sounds, loss of neurological plasticity, increased capacity to recall and store input, changes in motivation to learn and self-consciousness." | ||