| |||

Some Immediate Questions and Answers

(a) Why don't we just learn each other's languages? (b) What is the IAL? (c) Isn't English already the IAL? (d) Isn't Esperanto a perfectly adequate IAL? (e) Aren't there more than enough IAL projects already? (f) What kind of IAL might an international auxiliary language committee (IALC) select? (g) Why should an IALC choose a solution on the LangX model? (h) How could an IALC steer a developing IAL? (i) Would the IAL always remain in equilibrium with the mother tongues? (j) What is a language hierarchy?

(a) Why don't we just learn each other's languages? Until fairly recent times this idea definitely had merit: the average speed of travel being such that the vast majority of Earth's citizens were monolingual - very few coming into contact with more than a handful of languages during their lifetimes. Today of course there is more international exposure, not least via the Internet, and the drawbacks of multilingualism as a universal panacea have become apparent: human translation remains as expensive and potentially unreliable as ever, but mechanical translation has proved an inadequate substitute, and even an expert polyglot will still fail to master more than a fraction of the languages on offer.

An excellent brief summary of the potentialities of an IAL was given by 'Abdu'l-Bahá in a public talk nearly a century ago. He was referring to Esperanto, but made it clear on other occasions that Esperanto needed to be revised - a thought which also motivates the LangX project: "....the most important thing in the world is the realization of an auxiliary international language. Oneness of language will transform mankind into one world, remove religious misunderstandings, and unite East and West in the spirit of brotherhood and love. Oneness of language will change this world from many families into one family. This auxiliary international language will gather the nations under one standard, as if the five continents of the world had become one, for then mutual interchange of thought will be possible for all. It will remove ignorance and superstition, since each child of whatever race or nation can pursue his studies in science and art, needing but two languages - his own and the International. The world of matter will become the expression of the world of mind. Then discoveries will be revealed, inventions will multiply, the sciences advance by leaps and bounds, the scientific culture of the earth will develop along broader lines. Then the nations will be enabled to utilize the latest and best thought, because expressed in the International Language. If the International Language becomes a factor of the future, all the Eastern peoples will be enabled to acquaint themselves with the sciences of the West, and in turn the Western nations will become familiar with the thoughts and ideas of the East, thereby improving the condition of both. In short, with the establishment of this International Language the world of mankind will become another world and extraordinary will be the progress...." Edinburgh Esperanto Society, 7 January 1913 (printed in "Star of the West", Vol 4, No 2)

(c) Isn't English already the IAL for all practical purposes? Not really, though some of its proponents in the media might convey that impression. English does have semi-official status in a few specialised fields, including air and maritime telecommunications, but even there its use is far from universal. Having said that, it's undoubtedly true that English is the leading auxiliary language in the world today, and will continue as such for a long time to come - whatever is decided concerning the IAL. As for English itself being officially selected, we think it most unlikely - for historical political reasons, and because of an irregular spelling system which has proved highly resistant to reform. Moreover, as has often been pointed out, the pre-eminence of the English language relates more to the current status of English-speaking civilisation than to its inherent qualities. If the dominance of the English-speaking countries - which has arguably lasted from 1815 to the present - were to be superseded, the English language might consequently be expected to go the way of Ancient Greek, Latin, Arabic and French. The demise of the British Empire, the relative economic decline of America, the reversion of several ex-colonies to native languages, the establishment of rival languages in former English-speaking heartlands, and the continued political and cultural opposition to the English language from various quarters in several countries - all these are indications that the dethronement of English might already be proceeding.

(d) OK, an existing national language might not be the answer, but is there any doubt about the alternative? Esperanto remains way ahead of other constructed languages, and is a perfectly adequate IAL which only needs support. Esperanto's official adoption and consequent implementation through educational systems worldwide would be hastened if sites such as this promoted it. Esperanto is an excellent piece of work which will continue to inform and inspire the IAL movement in many ways. However, Esperanto has failed to gain the popular world-wide support necessary to become de facto IAL. An international auxiliary language committee (IALC) might extract the best elements from all languages and gradually combine them in a single evolving IAL. Dr Ludwig Zamenhof had a similar motivation in creating Esperanto 120 years ago, so in effect the IALC would be revising Esperanto. The sole-authorship of Esperanto and most other IAL attempts is actually the essence of their problem, given that one person can possibly know enough to create a new language. An internationally-representative committee (IALC), acting in consultation with all interested parties, has to be the minimum requirement.

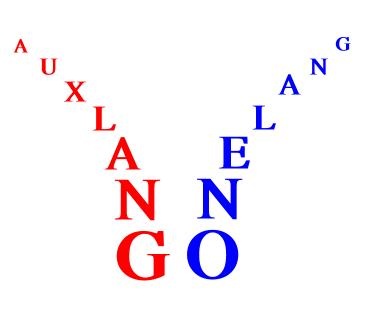

(e) Aren't there more than enough IAL projects already? Do we really need another? Rather than increasing the number of IAL projects by one, a better goal would be to eventually reduce them to one, by means of a hierarchy in which the best elements of all languages would find their place. The exact composition of this hierarchic global language cannot be known at this stage, so the name LangX suggests a void to be gradually filled in, under the guidance of the IALC.

(f) What kind of IAL might an international auxiliary language committee (IALC) select? Leaving aside the question of LangX for now, a solid consensus of opinion believes that the following linguistic attributes would be desirable in an initial IAL: (1) alphabetic script - logographic scripts take many times longer to learn (2) orthographic script - one-to-one correspondence between letters and sounds with no duplicated or silent letters (3) regular grammar, with the simplest possible rules, and no exceptions (4) no linguistic genders (5) an international vocabulary - with the eventual goal of words from as many languages as possible (6) no synonyms - only one word or name for each thing

(g) Why should the IALC choose a solution on the LangX model? The LangX model not only contains the six attributes listed above but also conforms to features validated by the only unconditionally-successful route to a new constructed common language: the historic sequence I have termed the jargon -> pidgin -> vernacular -> progression (JPVP). The only essential difference between the LangX model and the JPVP is that of scale, the former pertaining to the world in the immediate future, whereas JPVP sequences have occurred historically in discrete areas. There is no inherent reason why what has worked historically on a localised scale should not work in the near future on the global scale.

(h) How could the IALC create a language which is also evolving "naturally" in the body of users at the same time? It would be necessary to balance these potentially opposing tendencies. The IALC should be neither too active or prescriptive nor too passive or descriptive. The former might cause it to attempt to guide the language too rapidly, or in a direction the body of users were not prepared to take; the latter would allow for irregularity, such as had been sanctioned by mass usage. Harmonising these centralising and decentralising forces might not be easy, but a properly constituted committee, engaged in a continuous process of consultation with all interested parties, and taking a strictly (though not exclusively) scientific approach to all linguistic questions, should allow both centre and periphery to evolve together.

"East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet!" Was Kipling right? Will cultures always be essentially self-contained, so that no more than the most basic IAL will ever be required - or will both cultures and languages eventually merge? There are two schools of thought here. On the one hand, there are those who believe that, after the IAL is officially instituted, everyone will always and for all time speak at least two languages - the various mother-tongues for domestic consumption and the IAL for international communication. These hold that the primary focus of culture is national or ethnic, but that international agencies are necessary in order to support the requisite level of material civilisation - through trade, tourism, transport, communications, science, peace-keeping and the like. In other words, the international agencies deal in mundanities, whereas the more spiritual side of life - whether found through historic religions, secular philosophies, national treasuries of literature etc. - is not "global" or "international" in any real sense, since it is always linked to a particular culture or tradition. On the other hand are those who discount the possibility of self-sufficient or autonomous entities communicating indefinitely on a second-hand basis, believing that all languages will eventually merge into a single language by way of an official IAL, and claiming that this process is merely a conscious continuation of what is already occurring. Decades or centuries after the official IAL inauguration, everyone might still learn at least two languages at school, but they would expect the IAL to develop relative to the mother tongues. They would point to the precedent of pidgins and "creoles" ("vernacularised pidgins", here called "vernaculars"), inasmuch as pidgins were IALs on a smaller scale, formulated for essentially the same reason - the pertinent fact about pidgins being their tendency to become vernacularised: a process shown to derive from children learning and using the pidgin as a mother tongue. Thus, although pidgins were originally employed as purely auxiliary trading languages - second languages that nobody used as a mother tongue - children of certain traders, seafarers etc. evidently learned the pidgins as mother tongues, and elaborated them with borrowed or intuitive grammatical constructions and new words from various sources - exactly as tends to happen with mother tongues or primary languages in their developmental phase. Correspondingly, if the IAL were to begin its life essentially as a global pidgin, there is every chance that it would be elaborated by future generations in a similar way and for the same reasons. The modern world contains an ever-increasing number of itinerant key workers and administrative personnel employed by transnational corporations and international agencies. Such people would find such an IAL particularly useful, whether or not they possessed other second languages such as English, and consequently the children of some of them might well pick up the IAL as a mother tongue. The intuitive elaboration of the IAL might then be expected to follow, in concert with more formal and conscious innovative attempts by authors, advertisers, film-makers etc. who might well wish to write in the IAL directly in order to access the global market, the whole being co-ordinated and kept within acceptable bounds by the IAL committee. Assuming this process of development came to pass, the relationship between the IAL and every national tongue would be comparable to that which formerly existed between the minority ethnic tongues and the great national languages which entirely surrounded them. Thus, even as islands of minority ethnic tongues have been surrounded by a sea of English, every language would eventually find itself within the matrix of the IAL. And correspondingly, even as English formerly diluted and absorbed minority ethnic tongues in its midst, English would itself be absorbed, along with all other languages, into one universal tongue of enormous capacity and subtlety.

The history of the dogged survival of certain minority ethnic tongues clearly shows that such a process would never be achieved by force, rather would it happen for cultural and economic reasons. Thus, if speakers and writers were to deliberately use the international auxiliary language to reach the widest possible audience or readership, and listeners were to learn it - and tune into it - to keep up with the latest news and newest thought from anywhere in the world, there is little doubt that this common language would develop its own character as a truly global tongue, even as primary creative impetus went into it. If this did indeed happen - whether through neologism, transliteration, or other aspects of linguistic development - the national languages of the world could be expected to successively abandon their separate identities, over a period of centuries, in order to become part of it: in the same way that some minority ethnic tongues have hitherto become submerged in national languages. Thus there is no reason to suppose that an international auxiliary consciously developed for creative usage would not gradually obtain the linguistic and euphonic capacity to incorporate all useful features, whether structural or decorative, from both "national" and constructed languages. Indeed, it might well display these assets more precisely and harmoniously than their own more or less irregular grammars, partial phonologies and ramshackle orthographies. In such a scenario the mother-tongues would continue to be preserved in written and recorded form, but ultimately for sentimental value rather than linguistic information.

(j) What is a Language Hierarchy? A relatively advanced "Level 2" IAL such as Esperanto, though much easier to learn than irregular national languages, is still quite difficult for certain peoples - such as Chinese, English and Creole-speakers - whose grammar and/or phonology is less elaborate. For this reason it has been asserted that an introductory IAL for all the people of the world should be a simpler "Level 1" language. However, such an assertion might cause one to ask: "Wouldn't a Level 1 language - i.e. with a restricted and limited phonology, vocabulary and grammar - equate to a primitive and rudimentary tongue that few people would want to use?" To answer this question it is necessary to explain the LangX concept of a "language hierarchy". Such a hierarchy can be found within all languages, though it may be more noticeable among major languages. One aspect of the hierarchy exists within the lifespan of each individual, even as the infant normally progresses through babbled speech sounds to distinct words, then to a few words arranged in simple sentences, and finally to speech and then writing of increasing complexity. Having passed through these linguistic gradations, the individual might then use different levels of speech as appropriate. For instance, he might use simple words and sentences when addressing an infant but more complex language in academic circumstances. The same language is being used, but it is being employed hierarchically. In the social context, the same phenomenon may be described in terms of "registers" or "sociolects". Thus, a person may use his language as a basilect (restricted vocabulary and simple grammar), acrolect (advanced vocabulary and grammar), or somewhere in between (mesolect), according to the type of audience or, if writing, the intended readership. In practice there is considerable overlap and such gradations may be ill-defined, though they certainly exist as a recognised linguistic phenomenon. For instance, in West Indian English the acrolect is Standard English (even RP English) and the basilect a type of creolised English (or anglicised Creole), between which indigenous speakers are normally adept at switching, at least to some extent, according to whom they are addressing. A true world language would necessarily have a much greater scope than any national language, including in its hierarchy of registers. And now we come to an important point, which is that every person has normally learned simple words and sentences, but not all have progressed on to using their language in a sophisticated way. In other words, everyone in a community can understand and employ the basilect but not everyone is comfortable with all the mesolects, much less the acrolect The theory behind LangX is that the basilect or base level at any one time should be the official IAL, capable of being used and understood in any country, but that the progressively more differentiated and complex levels should only be used on the understanding that all such attempts were unofficial, experimental, and very possibly subject to drastic modification at a later date. Thus Lang25 would be gradually fixed during the initial time period, with the six levels up to and including Lang53 progressively fluid as they were "beta tested" - and with a particular focus on the next level Lang29. According to this hierarchic usage, an online dictionary might contain the core Lang25 vocabulary, but also six additional levels of vocabulary corresponding to Lang29 etc., of increasing provisionality. The different levels of words might be juxtaposed in the same dictionary, but colour-coded or otherwise differentiated. Similarly, cross-translation to as many languages as possible should focus on the base level (Lang25). Apart from the theoretical reasons already referred to there is also the practical consideration that a new script should be adopted in due course, or an existing one ratified. Levels of grammar, of increasing provisionality, might be published in the same way. As in childhood linguistic development, and the related establishment of pidgins, one might expect the greatest initial use of the IAL to be for relatively mundane purposes - for which no more than an elementary language would be required. But in any case the proposed restriction in the public and official usage of the upper registers should prevent the IAL separating into a vertical hierarchy of class languages just as invidious to global communication as the current horizontal pattern of national languages

| |||