| ||

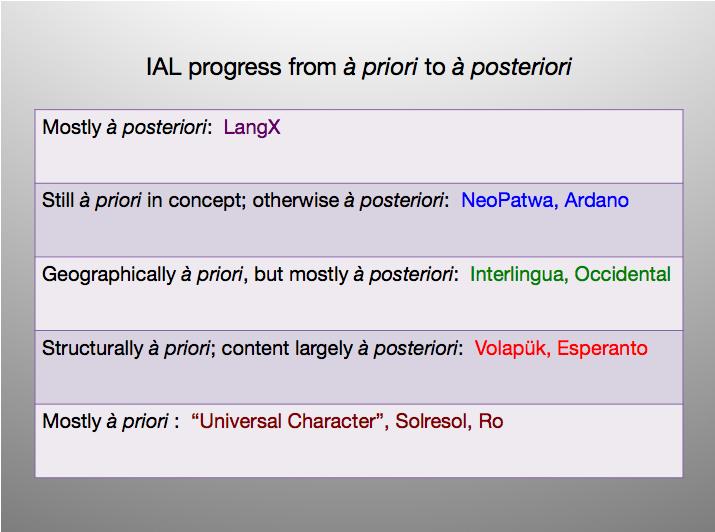

Of course, the idea of a new constructed IAL has been around for a very long time – so why hasn’t it been successfully realised by now? I have already referred to the link between language and culture. Language is an important influence, and people want to know who or what is behind it. The obscurity of constructed IAL origins is therefore an issue, and part of the reason why an IAL needs to be created by an appropriate global agency, in consultation with all interested parties. There is also the criticism that such tongues are artificial constructs if not outright fakes, and that a real language can only be formed by an entire people, according to the words and grammatical constructions which have proved popular over time. This criticism has some merit, but goes too far in that all existing mundane languages are more or less artificial anyway, given that they have influenced by orators, poets, neologists, grammarians, lexicographers and multitudes of nameless creative speakers and writers over the course of their history. So the line between so-called constructed and natural languages is not so great as is often claimed, even as judicious plant-breeding does not act contrary to nature, and may improve upon it. However, there is some truth to the claims of arbitrary construction and artifice. The constructed language movement itself recognises this, and has taken steps to correct the situation over the course of its history. Indeed, the remedy has come via the realisation that à priori attempts based on an inadequate knowledge of linguistics have been the problem, and that à posteriori constructions based upon what has already been proved within existing natural languages are a large part of the solution. And since all branches of knowledge have tended to advance in tandem, and language is intimately connected with many of them, it is no accident that progress of the IAL movement has roughly corresponded with international social and economic developments. Thus, the earliest à priori attempts tended to mirror the rather autocratic and arbitrary tenor of the times, as can be seen from the universal languages of Wilkins and Dalgarno in the context of the 17th Century. By the time Volapük and Esperanto appeared, towards the end of the 19th Century, a concession to existing speech elements reflected progress towards democracy. The well-known IALs of the mid 20th Century, Interlingua et al, were yet more naturalistic in following existing languages, but their main defect was a Eurocentrism corresponding to the prevailing political conditions. Indeed, it is only the latest generation of IALs – of 21st Century vintage – that have really started to be à posteriori in terms of global access. However, all these languages are still historically à priori in concept, inasmuch as they have been created by a single author. LangX – a new progressive IAL yet to be formed - should break this final limitation by moving to synthesis, the widest possible consultation, and collective authorship | ||